Neither landscape nor strictly abstraction, the ROADWORKS series exists somewhere between asphalt and autobiography. Drawing from the material grit of the street—tar, paint, fire-damaged objects—Rex and Edna of Volcan Studio reconfigure fragments of urban detritus into thick, sedimented surfaces that read like maps of psychological and physical displacement. These are not merely works made with materials from the street, but meditations on it: the street as archive, as witness, as mirror and increasingly, as a locus for sustainable artistic reclamation.

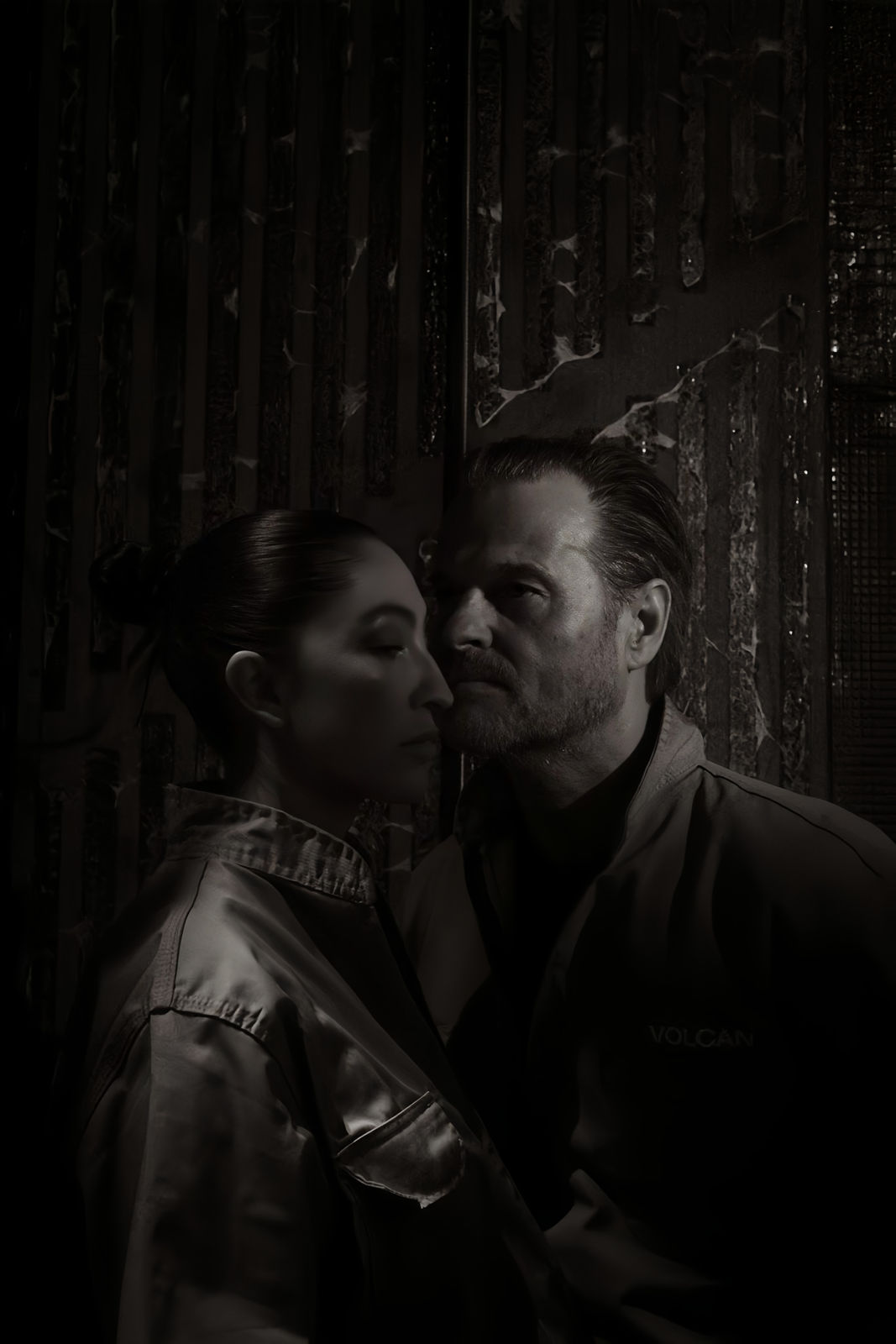

On the occasion of their new collaboration with Gallery Les Bois—a Chelsea-based space dedicated to environmentally engaged practices—Rex and Edna discuss how salvaged materials, conceptual clarity, and a commitment to sustainability shape their evolving practice. In this conversation, they discuss the intimacy of distance, the politics of reuse, and what it means to create work that’s both materially and emotionally resilient in a world on edge.

1. MATERIAL MEMORY OF STREETS

In works like 125 kilometers from home, the thick layering of tar and road paint creates a surface that feels almost topographical—an excavation of urban residue. Do you see these materials as carriers of memory, embedded with traces of the past, or do they serve more as raw matter, reshaped entirely by your hand?

These road materials, and roads in general, are rich with memory and history. Each layer of tar, paint, or urban fragment carries traces of the past, connecting us to the places, lives, and human experiences they’ve intersected with. That’s why we embrace upcycling—not just to transform these materials, but to preserve their connection to specific places and the stories they hold. Each piece we work with comes from a unique context, shaped by its geography and purpose. Through this process, we don’t just reinvent these materials; we honor their origins and the shared human experiences they continue to evoke.

2. NUMERICAL POETICS

Each piece in the ROADWORKS series carries a mathematically inflected title, such as 9.500 kilometres from hometo 1.200 kilometres from home. There’s a tension between the systematic precision of numbers and the raw physicality of your materials. Could you explain these numerical references—are they tied to specific histories, or do they function more as structural devices to read the work?

This series, though it might appear raw or rugged like the streets themselves, is deeply sentimental and rooted in personal stories. Each piece is tied to a very specific and meaningful experience. When we title a work, we choose a location that holds significance for Rex—places that marked his journey away from the hostile environment of his home. These distances are not just numerical; they represent points of transformation, spaces where he captured countless photographs that have played a vital role in the conceptualization of the series. The numbers, therefore, function as both structural references and deeply personal markers of memory and growth.

3. THE STREET AS SITE AND SUBJECT

In 16,700 Kilometres from home, the cracked, encrusted surface suggests erosion—both physical and perhaps psychological. Do you see the street as an archive to be excavated, not only as a site of external history but also as a self-portrait, expressive of your own journey?

In the ROADWORKS series, the street acts as both an archive and a reflection of personal experience. It’s not just about external history; it’s also about the journey within. The cracks, layers, and textures represent the erosion of time, both physically and emotionally. Each piece is like a self-portrait, reflecting the personal changes and challenges we’ve faced. The street, with all its imperfections and traces, mirrors the complexity of our own stories and the transformations we go through.

4. ARTE POVERA, RECONTEXTUALIZED

Your use of salvaged materials places ROADWORKS in dialogue with the Arte Povera tradition, particularly in its embrace of "low" or humble materials to subvert traditional artistic hierarchies. However, your handling of the canvas surface feels distinct and the tension between fragility and permanence is palpable. As sustainability becomes a more formalized and institutionalized focus within the contemporary art world, how do you view the role of your work in this context?

The materials we use, often considered “low” or discarded, have significant value and the potential for transformation. In a time when sustainability is becoming more central in the art world, our work isn’t just about reusing materials, but about reimagining their role in contemporary art.

These materials hold history, stories, and experiences, and by reclaiming them, we challenge the traditional art-making process that often overlooks the value in what’s discarded. Our aim is to give these materials new life, transforming them into art that connects the past with the present. Sustainability in the art world is usually seen from an environmental perspective, but we believe it’s also about questioning the systems that shape how art is made. By using salvaged materials, we offer a critique of overconsumption in both the art market and society. We want to shift the focus from novelty and perfection to the inherent value of what already exists. Through this process, our work becomes not just a reflection of sustainability, but a way to rethink the impact of art on the world and how it can be part of a more thoughtful, inclusive practice.

5. VENICE AND THE LANGUAGE OF VISIBILITY

With your participation in the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024, your work was seen on one of the most prestigious global art stages. The Biennale presents a paradox: it offers global visibility, but often through large-scale production, shipping, and spectacle—systems that sit uneasily with ideas of sustainability. From your perspective, what changes did you observe being made to address these tensions? Are productive conversations beginning to emerge around more sustainable ways of exhibiting on such a scale?

While the Venice Biennale remains one of the most prestigious platforms for artists, it undeniably raises questions about sustainability. The scale of production, shipping, and spectacle required to stage such an event generates a massive environmental footprint. Venice, with its limited infrastructure, struggles to accommodate the influx of visitors, putting pressure on transportation, hospitality, and logistics. The fact that all materials must be moved by water not only complicates installations but also significantly increases costs. Yet, amidst these challenges, positive developments are beginning to emerge.

For one, the conversation around sustainability is becoming more widespread and urgent at events like these. Additionally, the logistical difficulties and costs of sourcing materials on the island have encouraged more thoughtful practices. In our pavilion, and many others, packing materials were recycled and preserved, as replacements are hard to come by locally. This necessity has led to a heightened awareness of reusing and caring for resources. We don’t believe the solution is to abandon the Biennale, as it is deeply rooted in cultural history. Instead, the focus should be on integrating sustainability into its planning and execution, ensuring that this platform evolves responsibly while continuing to celebrate the arts.